NYT Crossword Clues sets the stage for a fascinating exploration of the art and craft behind these daily brain teasers. This guide delves into the intricacies of clue construction, analyzing their structure, difficulty, and the wordplay employed to challenge and delight solvers. We’ll examine the different types of clues, recurring themes, and the strategic use of language, vocabulary, and answer placement within the puzzle grid.

Prepare to unravel the secrets behind the seemingly simple, yet often surprisingly complex, world of the New York Times crossword puzzle clues.

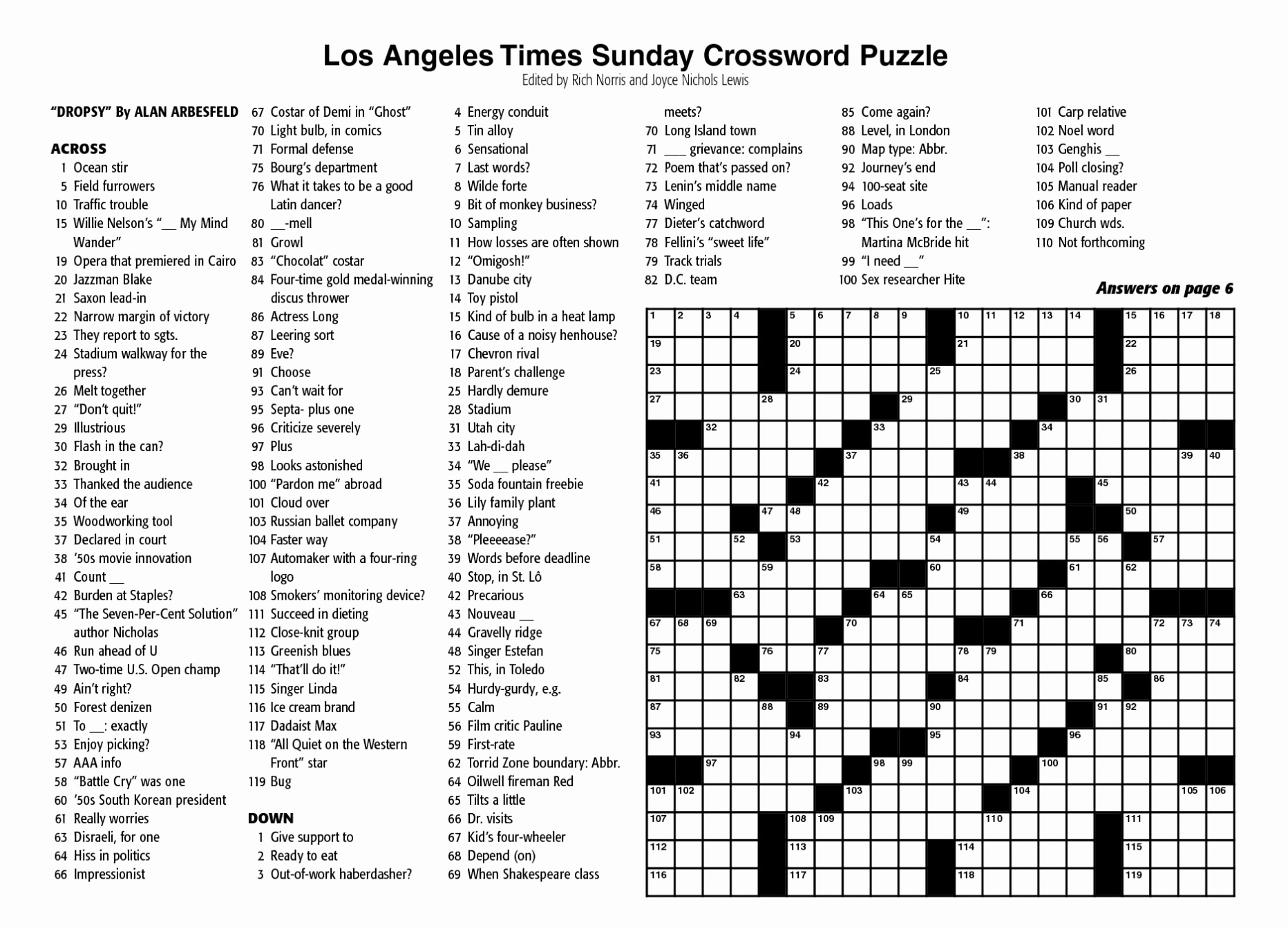

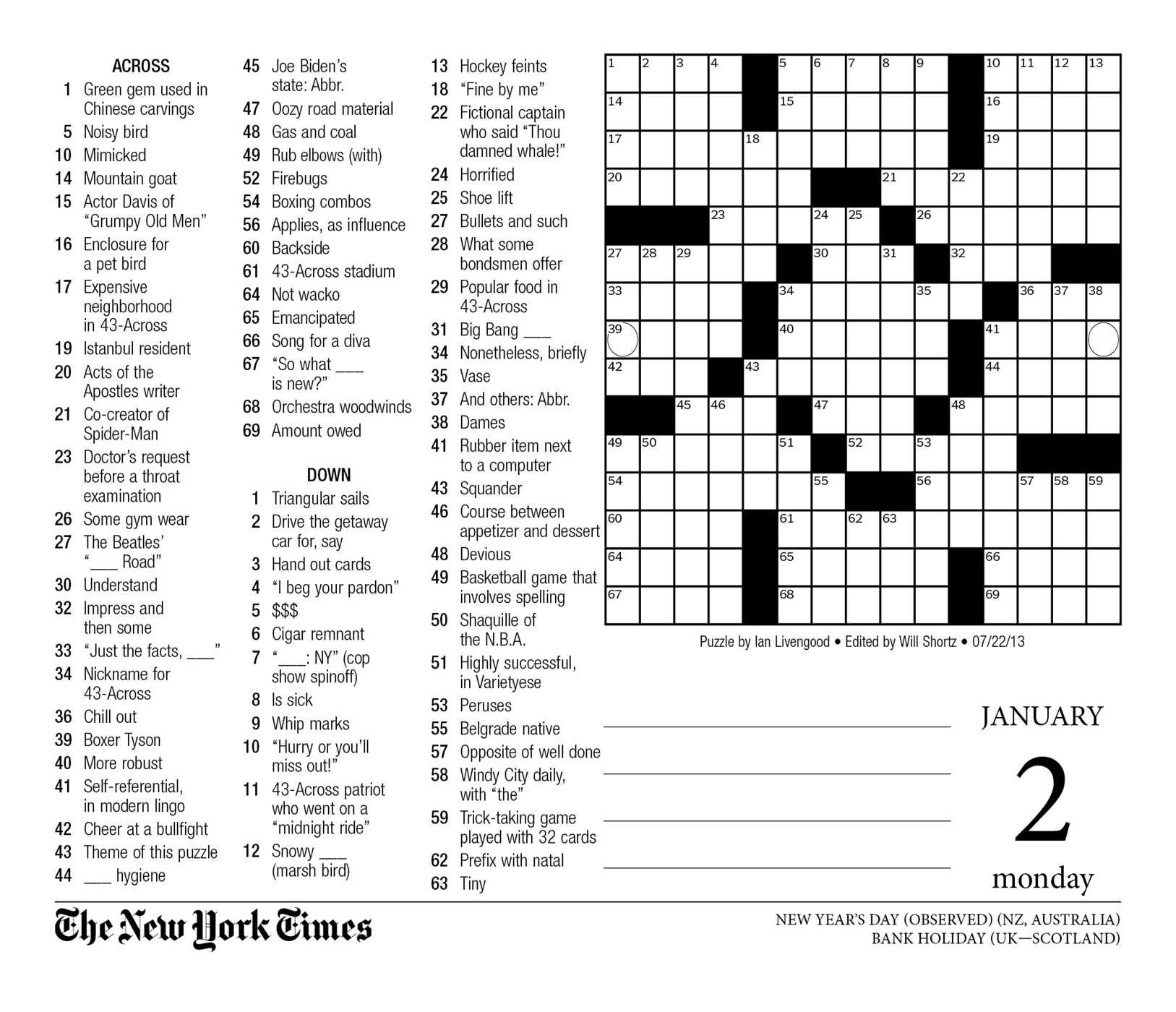

From the straightforward definition clues of Monday puzzles to the fiendishly clever cryptic clues of Saturday, we will analyze the various techniques used to create engaging and challenging crossword experiences. We’ll explore how clue length, wordplay, and the choice of vocabulary contribute to the overall difficulty and the solver’s satisfaction. By examining a large sample of NYT crossword clues, we will identify patterns, trends, and common strategies employed by the puzzle constructors.

Clue Difficulty and Structure

The New York Times crossword puzzle is renowned for its challenging and cleverly constructed clues. Understanding the structure and difficulty of these clues is key to successfully solving them. This analysis will explore the typical patterns in clue construction, compare the complexity across different days of the week, detail common wordplay techniques, and propose a system for classifying clue difficulty.The typical structure of a NYT crossword clue involves a definition, a wordplay element, or a combination of both.

Simpler clues, often found on Mondays, primarily rely on direct definitions. More complex clues, prevalent on Saturdays, integrate wordplay that requires solvers to think laterally and creatively. Variations in clue structure include cryptic clues, puns, anagrams, and hidden word clues, each adding layers of complexity.

Clue Complexity Across Days of the Week

Monday clues tend to be straightforward, often providing a direct definition of the answer. For example, a Monday clue might be “Large body of water” for OCEAN. In contrast, Saturday clues are significantly more challenging, often incorporating multiple layers of wordplay and requiring a deeper understanding of vocabulary and word construction. A Saturday clue might be “Sound of a broken record, perhaps?” for SCRATCH, relying on the double meaning of “scratch” and the listener’s knowledge of vinyl records.

This difference reflects a gradual increase in difficulty throughout the week, with Tuesday through Friday clues representing a progressive increase in complexity and wordplay.

Types of Wordplay in NYT Crossword Clues

The New York Times crossword utilizes a variety of wordplay techniques to create engaging and challenging clues. These include:

- Puns: These clues rely on the multiple meanings of a word or phrase. For example, “A Wright brother’s invention?” might be PLANE, playing on the dual meaning of “Wright” (referencing the Wright brothers) and “plane” (an aircraft).

- Anagrams: These clues present the letters of the answer scrambled, often with an indicator word suggesting the rearrangement. For example, “Disorganized team” might be for the answer “MATED,” which is an anagram of “TEAMED”.

- Cryptic Clues: These clues combine definition and wordplay in a more complex manner. They often involve cryptic instructions or hidden meanings. A cryptic clue might be “Head of state (5)” for “QUEEN,” where “head of state” is the definition, and “state” can be read as “state of being”, to find a “QUEEN” as a personification of a head of state.

- Hidden Word Clues: The answer is hidden within a larger word or phrase. For example, “Inside the bakery, there’s a delicious treat” might clue the answer “PIE” hidden within “bakery”.

A System for Classifying Clue Difficulty, Nyt crossword clues

A system for classifying clue difficulty could incorporate several factors:

- Clue Length: Longer clues tend to be more complex, often containing more wordplay or requiring more specific knowledge.

- Wordplay Type and Complexity: The type and number of wordplay elements used significantly impact difficulty. Cryptic clues are generally more challenging than simple puns.

- Common Knowledge Required: Clues requiring specialized knowledge or obscure vocabulary are inherently more difficult. For instance, a clue referencing a lesser-known historical figure would be harder than one referencing a common everyday object.

A numerical scoring system could be devised, assigning points based on these factors. For example, a simple definition clue might score 1 point, a pun 2 points, an anagram 3 points, and a complex cryptic clue 4 or more points. Adding points for clue length and the level of specialized knowledge required would further refine the difficulty score.

This system would allow for a more objective assessment of clue difficulty across different NYT crossword puzzles.

NYT crossword clues often require lateral thinking, demanding solvers to connect seemingly disparate concepts. For instance, consider a clue referencing corporate restructuring; this might unexpectedly lead you to consider the recent news regarding mosaic brands voluntary administration , a situation that could certainly inspire a challenging clue. Ultimately, the best NYT crossword clues surprise and delight with their clever wordplay and unexpected connections.

Language and Word Choice: Nyt Crossword Clues

The New York Times crossword puzzle, renowned for its challenging clues, employs a distinctive vocabulary and style. Clue construction hinges on a delicate balance between precision, wit, and the solver’s existing knowledge. The language used reflects this, often incorporating wordplay, misdirection, and subtle hints to guide the solver towards the answer. This careful selection of words is a crucial element in determining both the difficulty and the overall enjoyment of the puzzle.The vocabulary employed in NYT crossword clues ranges widely, drawing from both common and less frequently used words.

The constructors often leverage a broad spectrum of knowledge, encompassing areas like history, literature, science, and popular culture. This diversity contributes to the intellectual stimulation the puzzle offers, demanding solvers to tap into various aspects of their vocabulary and general knowledge.

Unusual and Archaic Word Usage

The NYT crossword frequently incorporates unusual or archaic words, adding a layer of complexity and intellectual challenge to the puzzle. These words are often cleverly woven into the clue, requiring solvers to decipher their meaning within the context of the puzzle. For instance, a clue might use “forsooth” (meaning “indeed” or “truly”) or “yclept” (meaning “called” or “named”), demanding a familiarity with less common vocabulary.

The inclusion of such words isn’t merely for obfuscation; it often adds a layer of elegance and sophistication to the clue, rewarding solvers with a deeper understanding of language. These less common words often appear in clues that are already considered more challenging. For example, a clue might use “choleric” (easily angered) instead of the simpler “angry,” increasing the difficulty and rewarding solvers with a more satisfying feeling of accomplishment.

Frequently Used Words and Phrases

Certain words and phrases appear with notable frequency in NYT crossword clues. These are often words that lend themselves well to wordplay or have multiple meanings. Understanding these common elements can aid solvers in recognizing patterns and anticipating potential answers.The following is a partial list of frequently used words and phrases:

- Part of speech indicators: “Kind of,” “type of,” “sort of,” “a,” “an,” “the”

- Words indicating synonyms or antonyms: “Opposite of,” “synonym for,” “like,” “similar to”

- Words indicating location or direction: “In,” “on,” “over,” “under,” “above,” “below”

- Words indicating time: “Before,” “after,” “during,” “past,” “present,” “future”

- Common abbreviations: “St.,” “Ave.,” “Mr.,” “Mrs.,” “etc.”

It is important to note that this is not an exhaustive list, and the frequency of specific words can vary over time. However, familiarity with these common elements can significantly improve a solver’s ability to decipher clues.

Word Choice and Clue Difficulty

The choice of words directly impacts the difficulty and solvability of a clue. Simple, straightforward language generally results in easier clues, while more complex vocabulary, obscure references, or intricate wordplay leads to more challenging clues. For example, a clue using common synonyms will be easier than one using less familiar words or obscure meanings. The use of misdirection, where the clue leads the solver towards an incorrect answer, is another technique that significantly increases difficulty.

Solving NYT crossword clues often requires lateral thinking, connecting seemingly disparate concepts. For instance, consider the challenge of finding a clue related to financial difficulties; you might unexpectedly find yourself researching news stories like the mosaic brands voluntary administration , which could inspire a clue about business restructuring or insolvency. Returning to the crossword, this unexpected connection can help unlock even the most challenging clues.

The skillful manipulation of language is therefore central to the construction of a well-crafted crossword clue. A clue that is too easy is unsatisfying, while one that is too difficult can be frustrating. The best clues strike a balance, providing a satisfying challenge without being insurmountable.

Answer Length and Placement

The distribution of answer lengths and their placement within the New York Times crossword puzzle grid are crucial elements impacting both the solver’s experience and the puzzle’s overall construction. Answer length directly influences clue writing, the grid’s symmetry, and the overall difficulty level. Understanding these relationships provides insight into the craft of crossword construction.Answer length significantly impacts clue construction.

Shorter answers (3-4 letters) often necessitate concise, straightforward clues, sometimes relying on cryptic or wordplay elements. Longer answers (8-15 letters and beyond) allow for more descriptive and nuanced clues, offering more flexibility to the constructor. This flexibility also allows for more thematic integration or the inclusion of less common vocabulary. For example, a short answer like “ERA” might require a highly concise clue, while a longer answer like “ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE” permits a more elaborate and potentially more challenging clue.

Answer Length Frequency

The following table presents a hypothetical frequency distribution of answer lengths based on a sample of 100 NYT crosswords. Note that these are illustrative figures and actual distributions may vary slightly depending on the specific puzzles analyzed. Obtaining precise data would require extensive analysis of a large corpus of published puzzles.

| Answer Length (Letters) | Frequency (out of 100 puzzles) | Answer Length (Letters) | Frequency (out of 100 puzzles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 150 | 8 | 70 |

| 4 | 120 | 9 | 60 |

| 5 | 100 | 10 | 50 |

| 6 | 90 | 11 | 40 |

| 7 | 80 | 12+ | 30 |

Placement of Longer Answers

Longer answers are typically strategically placed within the grid to maintain symmetry and facilitate the construction of intersecting words. They often appear in the central areas of the grid, providing a structural backbone around which shorter answers are woven. This central placement maximizes the impact of the longer answers and helps to balance the puzzle’s visual appeal and difficulty.

For example, a 15-letter answer might anchor the center of the grid, influencing the placement of many intersecting clues and answers. This central positioning also tends to create a more visually satisfying and balanced grid. The distribution of longer answers is not random; it is carefully planned to ensure both structural integrity and a pleasing aesthetic.

Visual Representation of Clue Data

Visual representations are crucial for understanding the complex relationships within NYT crossword clue data. By visualizing different aspects of the clues, we can gain insights into clue construction, difficulty, and the overall puzzle design. The following sections detail several visual representations that offer valuable perspectives on this data.

Clue Type Frequency

A bar chart effectively illustrates the frequency of different clue types. The horizontal axis would list the various clue types (e.g., cryptic, double definition, anagram, etc.), while the vertical axis would represent the count of each clue type. Each bar’s height corresponds to the number of clues belonging to that specific type. For example, a taller bar for “anagram” clues would indicate a higher frequency of this type in the dataset.

Data labels on each bar would show the exact count, enhancing readability. A title such as “Distribution of Clue Types in NYT Crosswords” would clearly convey the chart’s purpose. The chart could also include a legend if necessary, especially if color-coding is used to differentiate clue types.

Clue Length and Difficulty Relationship

A scatter plot is the most suitable visual representation to show the relationship between clue length and difficulty. The horizontal axis would represent clue length (in words), and the vertical axis would represent clue difficulty (measured on a scale, perhaps 1-5, with 5 being the most difficult). Each data point would represent a single clue, its position determined by its length and assigned difficulty.

A trend line could be added to the scatter plot to show any correlation between clue length and difficulty. A positive correlation would suggest longer clues tend to be more difficult, while a negative correlation would suggest the opposite. The plot title could be “Correlation Between Clue Length and Difficulty.” Clearly labeling the axes and including a legend explaining the difficulty scale are crucial for easy interpretation.

Distribution of Answer Lengths

A histogram is ideal for illustrating the distribution of answer lengths across the crossword grid. The horizontal axis would represent the answer length (in letters), and the vertical axis would represent the frequency of answers with that length. Each bar’s height would correspond to the number of answers with the length indicated by the bar’s position on the horizontal axis.

For example, a tall bar at “5” would signify a high frequency of five-letter answers. The histogram would provide a clear picture of the answer length distribution, highlighting the most common answer lengths used in the puzzle. A title such as “Frequency Distribution of Answer Lengths in NYT Crosswords” would appropriately label the visualization. Clear labeling of axes and the use of a visually appealing color scheme would make the histogram easily understandable.

Understanding the nuances of NYT crossword clues unlocks a deeper appreciation for the creativity and skill involved in their construction. This guide has provided a framework for analyzing clue structure, identifying common patterns, and recognizing the various types of wordplay used. By understanding these elements, solvers can enhance their skills and approach the daily challenge with greater confidence and insight.

Whether you’re a seasoned crossword aficionado or a curious newcomer, the journey into the world of NYT crossword clues is a rewarding one, filled with intellectual stimulation and satisfying moments of discovery.

Top FAQs

What is the average difficulty of a NYT crossword clue?

The difficulty varies greatly depending on the day of the week. Monday puzzles are generally easier, while Saturday puzzles are significantly more challenging.

Are there resources available to help me improve my NYT crossword solving skills?

Yes, many online resources, including websites and forums dedicated to crossword puzzles, offer tips, strategies, and explanations of clue types.

How are NYT crossword clues created?

NYT crossword clues are created by professional constructors who follow specific guidelines regarding wordplay, difficulty, and overall puzzle coherence.

What makes a good NYT crossword clue?

A good NYT crossword clue is fair, engaging, and cleverly worded. It should provide enough information to lead to the answer without being overly obscure or misleading.